Standard diabetes test may mislead diagnosis in S Asians, including Indians: Lancet

Feb 09, 2026

New Delhi [India], February 9 : The widely used glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test may not accurately reflect blood glucose levels for millions of Indians, according to a new evidence-based viewpoint published online in the Lancet Regional Health.

The crucial HbA1c test measures average blood sugar levels over the past two to three months by checking the percentage of haemoglobin coated with glucose. A normal range is below 5.7 per cent, while prediabetes is 5.7 per cent to 6.4 per cent, and diabetes is greater than or equal 6.5 per cent.

The study published in the Lancet Regional Health: Southeast Asia on February 9, 2026, revealed spurious results in the HbA1c test in populations with high prevalence of anaemia (endemic in India), hemo-globinopathies and red blood cell enzyme (G6PD) deficiency.

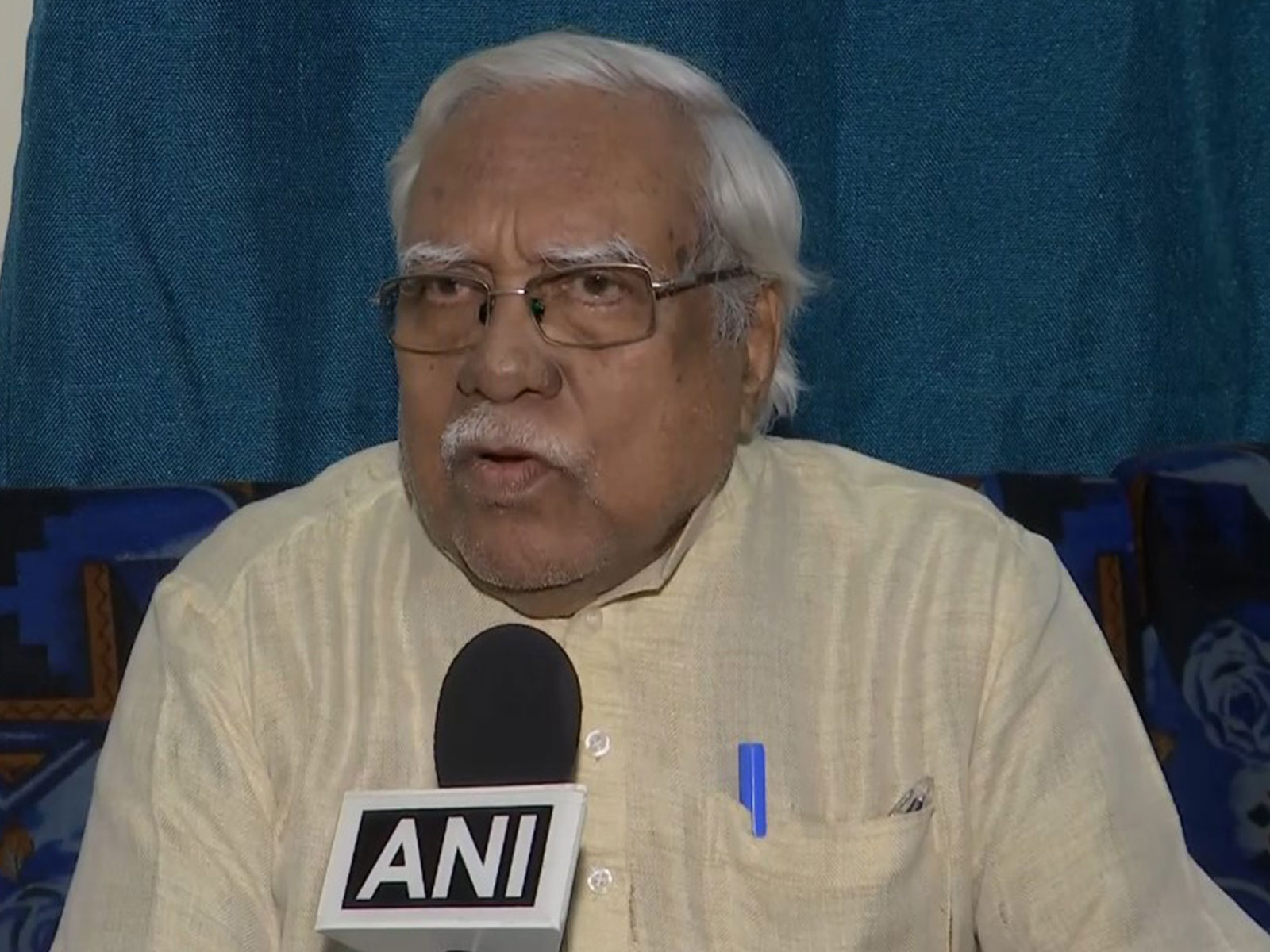

Led by Professor Anoop Misra and collaborators, the review questions reliance on HbA1c as a sole diagnostic or monitoring tool for type 2 diabetes in South Asia. HbA1c measurements primarily reflect the glycation of haemoglobin. Any condition that affects the quantity, structure, or lifespan of haemoglobin -- such as anaemia, haemoglobinopathies, or other red blood cell disorders -- can distort HbA1c values and lead to misleading estimates of average blood glucose.

"Relying exclusively on HbA1c can result in misclassification of diabetes status," said Professor Anoop Misra, corresponding author and Chairman of Fortis C-DOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes. "Some individuals may be diagnosed later than appropriate, while others could be misdiagnosed, which may affect timely diagnosis and management. Similarly, monitoring of blood sugar status may be compromised," he said.

Shashank Joshi, co-author from Joshi Clinic, Mumbai, added: "Even in well-resourced urban hospitals, HbA1c readings can be influenced by red blood cell variations and inherited haemoglobin disorders. In rural and tribal areas, where anaemia and red cell abnormalities are common, the discrepancies may be greater."

Dr. Shambho Samrat Samajdar, co-author from Kolkata, emphasised a comprehensive approach: "Combining oral glucose tolerance test, self-monitoring of blood glucose, and hematologic assessments provides a more accurate picture of diabetes risk. This approach can help refine public health estimates and guide resource allocation."

HbA1c may under- or overestimate blood glucose in populations with high rates of low blood counts (anaemia), inherited blood disorders (abnormal haemoglobin), or enzyme problems like G6PD deficiency anaemia and hemoglobinopathies.

In some regions of India (more than 50% population in some regions, data from 2025), people are nutritionally challenged with widespread iron deficiency anaemia, which can distort HbA1c readings. This would affect both diagnosis and monitoring, thus misleading clinicians.

Reliance on HbA1c alone could delay diagnosis by up to four years in men with undetected G6PD deficiency, potentially increasing the risk of complications.

In addition, inconsistent quality control across laboratories can further affect HbA1c accuracy, making interpretation challenging. Public health surveys based solely on HbA1c may misrepresent India's diabetes burden.

The authors outline a resource-adapted framework for India: in low-resource settings, oral glucose tolerance test (two glucose values, one fasting and another 2 hours after ingesting 75 gm glucose) for diagnosis, and for monitoring self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG, using glucose meters) two to three times weekly combined with basic hematologic screening (hemoglobin, blood smear) is recommended.

In tertiary care settings, a combination of HbA1C (done with standard equipment) with OGTT for diagnosis and for monitoring, and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with alternative markers like fructosamine.

When needed, comprehensive iron studies, haemoglobin electrophoresis, and quantitative G6PD testing are advised.

The framework emphasises that monitoring intensity and biomarker selection should be tailored to healthcare resources and patient risk factors, with particular attention to populations where anaemia, hemoglobinopathies, and G6PD deficiency are prevalent.

In regions where anaemia from various causes is endemic (such as India), glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), being derived from haemoglobin and widely regarded as the gold standard for monitoring diabetes, may yield spurious values; therefore, in many cases, it should be combined with other tests for the diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes.